| ||||

|

|

ESSAYS - 2025 ESSAY In 2003, two brief pieces appeared on the site to fill what was then a new section. Over the years a theme developed, and now the essays in most cases deal with some aspect of technological change, usually with a consumer bent. In past summers, anywhere from one to four essays have been posted during the summer. In 2024 there was one essay, and it has been added to the Essay Archives. The Essay Archives contain links to all essays which have appeared on the site since its inception. See details about viewing past essays on the Essay Archives main page. The 2025 essay is included below.

RARE EARTHS: IN NEED OF A DOMESTIC MEDIUM TO BE WELL-DONE IN THE U.S. The terms "rare earth" and "rare earth elements" have appeared frequently in the news so far this year. On February 14, President Trump signed an Executive Order establishing the National Energy Dominance Counci. The Council was formed to advise the President on energy-related matters, including critical minerals, a term which includes rare earth elements. (n1) That order was followed by another on March 20 to boost American mineral production, streamline permitting and enhance national security. (n2) In the order, three things were noted, among other items. First, it was stated that the Defense Production Act (DPA, a Cold War-era law) would be used to expand domestic mineral production capacity. (n3) It was also stated that China, Iran and Russia control large deposits of several minerals critical to the U.S., posing a security risk (about 70% of U.S. imports of rare earths come from China) (n4) and that the demand for critical minerals has been dubbed the "gold rush of the 21st Century" due to their importance in emerging technologies. (n5) But that is not all. In the beginning of April, China placed export restrictions on rare earth elements as part of its response to U.S.-imposed tariffs, including "not only mined minerals but permanent magnets and other finished products that [are] difficult to replace." (n6) The exports on which China placed restrictions were "vital to the military and tech industries . . . [and] the rare earths standoff represents a new front line in economic warfare between the U.S. and China." (n7) Though that conflict was resolved, other matters regarding mineral production emerged. After a public dust-up in the Oval Office between President Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the U.S. and Ukraine went on to sign a minerals deal giving the U.S. access to reserves of rare earth elements, among other things, within Ukraine. The deal was signed on April 30. (n8) Most recently, early in July the Trump administration put into effect what was stated in the March Executive Order, using the DPA to sign a "multibillion dollar deal to become the biggest stakeholder in a Las Vegas-based company operating the nation's only rare earth mine," MP Materials. (n9) The Department of Defense (DoD, now referred to as the Department of War), did not hold a press conference to announce the massive spending commitment. The details appeared in the company's July 9 Form 8-K filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). In that filing MP Materials announced that it had "entered into definitive agreements establishing a transformational public-private partnership with the United States Department of Defense . . . a multibillion-dollar package of investments and long-term commitments . . . [including] a $400 million equity investment by the Department of Defense in newly authorized and issued Series A Preferred stock, . . . a commitment for up to $350 million in additional funding in the form of additional Series A Preferred Stock, a commitment for a $150 million loan to support expansion of heavy rare earth separation to be extended by the DoD within 30 days following the Closing," and more. (n10) According to some industry experts, the use of the DPA is allowing the megadeal to be forwarded "unburdened by the Federal Acquisition Regulation, Cost Accounting Standards, the Competition in Contracting Act and the Truthful Cost or Pricing Data Statute." (n11) Matthew Zolnowski, "president of the supply chain consulting firm Greyfriars LLC, said that while the provisions of the DPA authorize the DoD to circumvent existing laws, the agency still has to comply with the Anti-Deficiency Act, a federal law that bars agencies from spending or obligating more money than Congress has appropriated. [He] said congressional appropriators should scrutinize the deal, which appears to cost about $3.5 billion - an amount that he said exceeds current appropriations to the DPA fund even when considering the GOP megabill's addition of $1 billion." (n12)

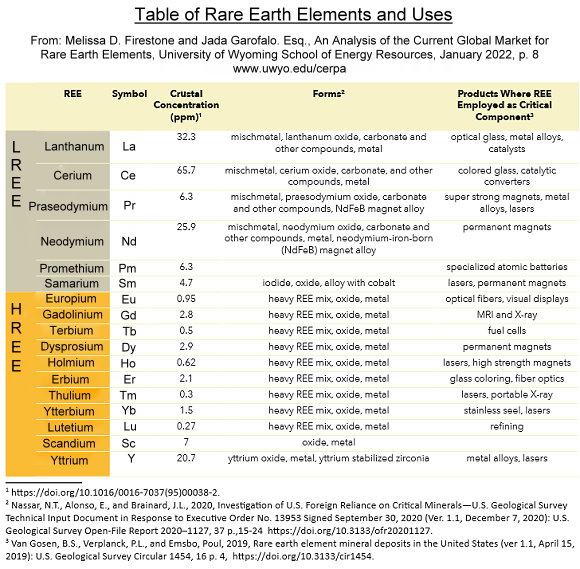

Aerial view of the Mountain Pass Mine, operated by MP Materials. The mine is located southwest of Las Vegas off the I-15 in San Bernardino County, California. Photo credit: MP Materials. So what exactly are rare earths or rare earth elements, and why are they worth billions of dollars? Answers to those questions will be provided in the following portions of the essay. Rare Earth Elements The 17 rare earth elements (REE, also referred to as rare earths or rare earth metals) are soft heavy metals classified as the 15 lanthanides (number 57 - 71 on the periodic table) plus scandium (21) and yttrium (39), which tend to occur in the same deposits and have similar chemical properties. Rare earths can be further classified as Light Rare Earth Elements (LREE) and Heavy Rare Earth Elements (HREE). The biggest misnomer from the name comes with the word "rare," for the rare earths actually are fairly abundant in the earth's crust. "Even the two least abundant REE (Thulium and Lutetium) are nearly 200 times more commom than gold. However, in contrast to ordinary base and precious metals, REE have very little tendency to become concentrated in exploitable ore deposits. Consequently, most of the world's supply of REE comes from only a handful of sources." (n13) In most of the large-scale and economically-feasible deposits of REE that have been found and mined to date, REE tend to be found grouped together. Separating and purifying individual rare earth elements, each with its own properties and uses, is an intensive and complex process which in some cases can produce toxic or radioactive waste. For example, "monzanite, the single most commom REE material, generally contains elevated levels of thorium. Although thorium itself is only weakly radioactive, it is accompanied by highly radioactive intermediary daughter products, particularly radium, that can accumulate during processing. Concerns about radioactivity hazards has now largely eliminated monzanite as a significant source of REE and focused attention on those few deposits where the REE occur in other low-thorium minerals, particularly bastnaesite." (n14) Still, in one estimate of REE mining and separation/purification processes in China, it was noted that "mining just one tonne of rare earth minerals creates some 2000 tonnes of . . . waste." (n15) By one estimate, at Mountain Pass, roughly 8 to 10 percent of the mined rock contains rare earths. (n16) [A 1954 technical report by the U.S. Department of the Interior/USGS evaluating the mine area titled Rare Earth Mineral Deposits of the Mountain Pass District, San Bernardino County, CA, can be found at https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0261/report.pdf.] A chart showing the 17 rare earth elements and some of their uses is included below.

The chart above provides examples of some generalized uses of REE. However, if you drive an electric car like a Tesla, talk on an Apple phone, need an MRI, fly a drone or even watch TV, then REE are part of your daily existence. From a government standpoint, the elements also play vital roles in our nation's weapons systems and technologies. Almost no equivalent or equally effective substitutes exist for any of the rare earths in the products in which they are used. The eight-minute video below, though created four years ago, summarizes the predicament many companies and governments have come to face amid the dominance of China in REE mining, processing and trade. But it wasn't always that way. For many years, beginning around the mid 1960s, the US was the REE leader. How did things change? Ironically, the story is tied in part to the history of the Mountain Pass Mine.

REE in the US and the History of the Mountain Pass Mine During World War II, U.S. scientists developed certain rare earth separation techniques as part of the Manhattan Project. Much of the research into rare earths continued after the war at Ames Laboratory in Iowa. Until that time, "most of the world's rare earths were sourced from placer sand deposits in India and Brazil. In the 1950s, South Africa was the world's rare earth source from a monzanite-rich reef at the Steenkampskraal mine in Western Cape province." (n17) Deposits containing rare earths were first discovered in California in 1949 in the area that became the Mountain Pass Mine. The prospectors who found the deposit sold their claim to the Molybdenum Corporation of America, later called Molycorp. (n18) (Molycorp filed for bankruptcy in 2015, was purchased and then reorganized as Neo Performance Materials - www.neomaterials.com) Molycorp began mining operations at Mountain Pass, and from about the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s, became a global leader in REE production. After that time, a few things began to change, both in the US and abroad in China. First, in the U.S. "In 1960, the United States consumed 1600 tonnes of the specialized metals, a number that had jumped to 20,900 tonnes by 1980 . . . All this growth did not go unnoticed by Wall Street or China. In 1977, the Union Oil Company of California, known as Unocal, bought Molycorp for $240 million ($1.25 billion in 2023 dollars) and said it would operate the company as a stand-alone entity." (n19) This purchase took place over the backdrop of other factors. First, afer the Cold War, "the U.S. Defense Department determined that 99 percent of its national defense stockpile of critical minerals and rare-earth elements - which, at its peak, was worth nearly $42 billion (inflation-adjusted) - was surplus. So the Defense Department sold it off, switching to just-in-time-global sourcing." (n20) As indicated in the video above, China also had taken note of the rise in value of REE, and Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping indicated sentiments that rare earths could become to China what oil was to the Middle East. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1970, and as a result, by one author's account, "regulatory pressure on the U.S. rare earths industry [intensified] . . . California's mine owners found themselves running up against environmental regulations and, in at least one way, consciously violating them. In 1980, Molycorp built a 14-mile pipeline to the nearby Ivanpah Lake, a dry lake bed that straddles Interstate 15 on its way to Las Vegas. While the company's wastewater disposal permit allowed saltwater to be sent through the pipeline to Ivanpah evaporation ponds, for the next sixteen years Molycorp sent wastewater it knew was infused with radioactive particles and heavy metals from the rare earth production process onto the lake bed. Between 1984 and 1993, forty spills totaling 720,000 gallons were caused by Molycorp's Mountain Pass facility . . . Efforts to clean the pipe in the summer of 1996 caused even more ruptures that had leaked 380,000 gallons of radioactive water into the Mojave Desert . . . Amid the mounting regulatory pressure, Molycorp announced an ambitious plan in the spring of 1999 to slash the amount of water it used by 62 percent and the amount of wastewater it generated by 50 percent, part of what it saw as a 30-year plan . . . [However,] broader market forces intervened, spurred by intense Chinese pricing pressure. The site closed in 2002, its equipment left to rust in the warm California sun." (n21)

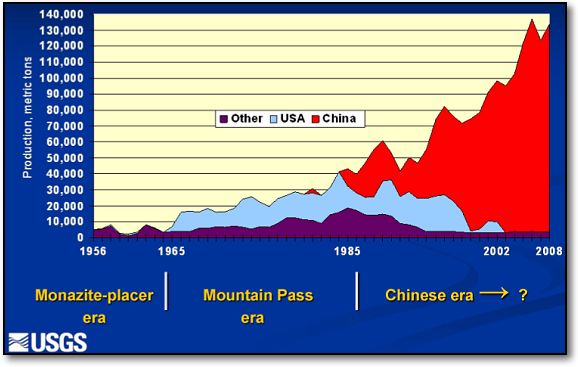

Global rare earth-oxide production trends. US Geological Survey (USGS) graph from D.J. Cordier (USGS), 2011, update from Haxel and others, 2022. From Pui-Kwan Tse, China's Rare-Earth Industry, Reston, Virginia: U.S. Department of the Interior/USGS, Open-File Report 2011-1042, 2011, p. 3 The Rise and Global Dominance of China's Rare Earth Industry The largest rare earth mine in the world is located in China at Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia. The area was discovered in the 1920s and mining began there in 1957; Bayan Obo is estimated to contain almost 40% of the world's known rare earth reserves. (n22) In addition to area around Bayan Obo, rare earth resources also have been found in 21 of China's Provinces and Autonomous Regions. (n23) Beginning in 1990, "the Chinese Government declared rare earths to be a protected and strategic mineral. As a consequence, foreign investors are prohibited from mining rare earths and are restricted from participating in rare-earth smelting and separation processes except in joint ventures with Chinese firms." (n24) While in 1990 China produced about 27 percent of world output of REE, by 2008 that figure had jumped to over 90 percent. (n25) Though global dynamics have changed somewhat since then, in 2023 China still produced almost 70 percent of global REE, followed by the U.S. at 12.3 percent, Myanmar at 10.9 percent and Australia at 5.1 percent. (n26) Some of this global shift stemmed from events beginning in about 2010. Around 2010, signs began to emerge in the area around Bayan Obo of severe pollution affecting both local residents and the environment. A BBC reporter's more recent visit to the area is documented in the video below. The note of mounting environmental issues in that 2010 time frame, however, prompted China's State Council to write that "the country's rare earth industry was causing 'severe damage to the ecological environment' . . . Faced with these mounting environmental disasters, as well as fears that it was depleting its rare earth reserves too rapidly, China slashed its export of the elements in 2010 by 40 percent. The new limits sent prices soaring and kicked off concern around the globe that China had too tight of a stranglehold on . . . the elements." (n27) But at that time there were few other places around the globe where REE could be sourced.

In subsequent years, China sought to further consolidate the country's REE industry under government control. The Chinese government shifted its policy strategy to "seek global dominance in rare earths not through controlling the volume of outputs, but instead by controlling which firms could operate." (n28) It launched "an ambitious, and often ruthless, effort to winnow down the entire rare earth industry to just six consolidated companies . . . Within four years China . . . announced the closure of dozens of smaller mining and refining companies and guded the mergers of surviving companies into six supersized, mostly state-owned firms, nicknamed the Big Six . . . Through the Big Six, China could . . . largely control both supply and price." (n29) It was in this changing global environment that thoughts of re-opening the Mountain Pass Mine emerged. A U.S. Presence Again in the Global REE Industry In 2017 a consortium called MP Mine Operations bought the Mountain Pass facilities in an auction of what had been Molycorp's assets. The consortium included Chicago hedge fund JHL, led by Jim Littinsky, investment fund QVT Financial and the Chinese rare earths company Shenghe Resources Holding Co. Ltd. That consortium would later become MP Materials (www.mpmaterials.com), and by 2020 Mountain Pass mine was once again up and running. While it may seem odd that in order to compete against China a U.S.-led company would partner with a Chinese one, that became a necessity for a couple of main reasons. First, "MP's two American investors had no experience in minings, but Shenghe did, as it was one of the largest rare earths companies in the world." (n30) The second is something that one author refers to as the "Achillies heel" of the rare earths supply chain, that no final REE processing and separation facilities exist in the U.S. and "all rare-earth elements are sent to China for refining and processing." (n31) USGS statistics show that in 2024 45,000 metric tons of rare earth mineral concentrates were produced in the U.S. and 43,000 metric tons of rare earth ores and compounds were exported (n32), because in order to produce a final metal able to be used by industry the ores/compounds must be sent to China for processing. MP's agreement with Shenge relies "on Shenghe to process all the rock . . . dug out of the California desert . . . [which means] shipping roughly 40,000 tonnes of concentrated rare earths per year from California to China. As part of the deal, Shenghe would get to keep all of MP Materials' profit until it recouped its initial $50 million investment." (n33) MP Materials does have plans in the works for both a processing facility and a magnet production facility, but neither of those are yet up and running. The video below introduces MP Materials and its current operations as well as future plans, but before presenting that, it may be necessary to explain the full product cycle of REE from mining to finished product. The five steps from REE mine to finished product are 1) mining, 2) concentration, 3) separation, 4) processing and 5) manufacturing. In the first step, mining, rare earth ores are extracted from the ground, as is currently being done at the Mountain Pass mine. The second step, concentration (also referred to as beneficiation) is "a process where mined ore is reduced in size to increase its economic value . . . [this] typically includes crushing the ore and separating the rare earth oxides by flotation, magnetic or gravimetric separation . . . A tremendous amount of discarded waste rock (tailings) is generated in this process and is typically managed onsite . . . Chemical changes typically do not occur during the first step and this process is ususally situated near the mine site to reduce transport costs." (n34) These concentrates are what is being produced at the Mountain Pass mine and then exported to China for further processing. The third step, separation "refers to the process of separating individual REEs from one another in the mined concentrates in the form of rare earth oxides (REOs). Separation of REEs is chemically intensive because the REEs are very chemically similar to one another . . . thorium is removed at this stage, introducing both risk and cost associated with waste storage/disposal. Solvent extraction is the most common method of separation used in the industry." (n35) The fourth step is processing, and processing "refers to the conversion of REOs to rare earth metals . . . which can then be used to form alloys . . . using metallurgical processes like sintering. Molten salt electrolysis is the conventional process for conversion to metals." (n36) In the United States up until this time there has been no capability for REE separation and processing, which is why the product produced at Mountain Pass Mine is shipped to China. In the final step, manufacturing, the processed metals are sold to customers for use in their products, meaning the either the metals or finished products containing the metals must be shipped from China to their final destinaton.

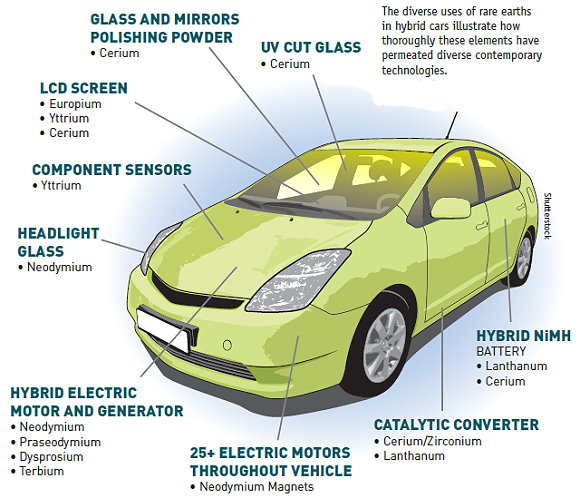

Currently the Mountain Pass Mine is the only operational REE mine in the U.S. However, there are other projects in the works. Recent statistics show that while measured/indicated resources of rare earths in the U.S. are estimated at about 3.6 million tons, they are estimated to be more than 14 million tons in Canada (n37) (which may in part have fueled President Trump's expressed desire for making Canada the 51st state). Some other rare earth projects in the U.S. in various stages of exploration, permitting or seeking funding include: Elk Creek Project, Nebraska - NioCorp Development Corp. (www.niocorp.com) Round Top Project, Texas - Texas Mineral Resources Corp. (www.tmrcorp.com) Bokan Mountain Project, Alaska - Ucore Rare Metals, Inc., (www.ucore.com) Bear Lodge Project, Wyoming - Rare Element Resources Ltd., (www.rareelementresources.com) La Paz Project, Arizona - American Rare Earths Ltd., (www.americanrareearths.com) Other companies in addition to MP Materials also are beginning to try to close the separation/processing gap, with the first rare earth metals to be produced commercially in the U.S. coming from Massachusetts-based Phoenix Tailings (www.phoenixtailings.com). The company claims to have a "novel proprietary process that produces [the rare earth metals] with zero toxic byproducts and zero direct carbon emissions" (n38) using mine waste, or tailings, as a base product. How Are Rare Earth Metals Used? The needs for and uses of REE in today's technologies has changed remarkably since one of the most common uses for rare earths in the early post-World War II period: enhancing colors on glass screens in color TVs. Today, "the diverse nuclear, metallurgical, chemical, catalytic, electrical, magnetic and optical properties of the REE have led to an ever-increasing variety of applications. These uses range from the mundane (lighter flints, glass polishing) to high-tech (phosphors, lasers, magnets, batteries, magnetic refrigeration) to futuristic (high-temperature superconductivity, safe storage and transport of hydrogen for a post-hydrocarbon economy). (n39) The diagram below, though somewhat older and showing a hybrid car, gives an idea of some of the different types of components in which rare earths are used in the automotive industry. Those uses, particularly for magnets, have become even more significant as the sales and demand for fully electric cars has continued to grow.

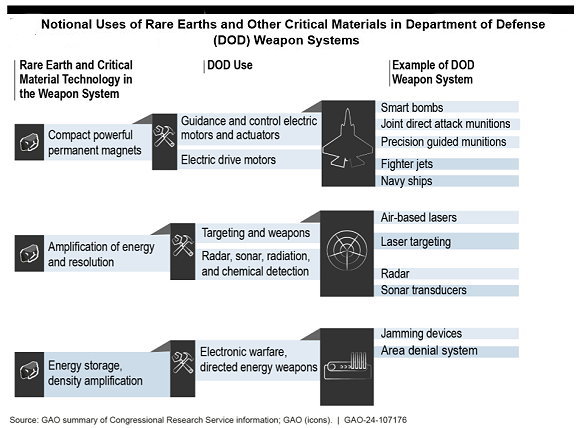

Source/Chart Credit, Larry Borowsky, "Sourcing Rare Earths and Critical Materials," Mines Magazine, online at https://minesmagazine.com/1737. Of particular concern to the U.S. government is the growing need for REE in uses vital to national security, particularly as building blocks in a wide range of weapons systems. The Department of Defense (DOD), has "assessed that it faces sigificant risks in its supply chains for these materials and that there would be a high potential for harm to national security in the event of supply chain disruptions. Of particular concern, most of these materials are mined and processed in China, which makes DOD's weapons system programs vulnerable to supply chain disruptions by an adversary nation." (n40) The chart below shows some of the materials and their uses in a variety of our nation's weapons systems.

Chart Credit: U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), "Critical Materials: Action Needed to Implement Requirements That Reduce Supply Chaine Risks," GAO-24-107176, Q&A Report to Congressional Committees, September 10, 2024, p. 3. Probably the most important use of REE at this time is in permanent, ultra-strong magnets. The production of permanent magnets accounted for more than 45 percent of global demand for REE in 2023. (n41) What are these magnets, and why are they so valuable? There are two main types of these magnets, with the rare earth element listed in bold letters: neodymium-iron-boron magnets, which are the most powerful, and samarium cobalt magnets. "A three kilogram neodymium alloy magnet can lift objects that weigh over 300 kilgrams . . . [They also] generate vibrations in smartphones, produce sounds in earbuds and headphones, enable the reading and writing of data in hard disk drives and generate magnetic fields used in MRI machines. And adding a bit of dysprosium to these magnets can boost the alloy's heat resistance, making it a good choice for the rotors that spin in the hot interiors of many electric vehicle motors." (n42) Samarium-cobalt (SmCo) magnets "are slightly weaker in raw strength but excel in high-temperature performance and corrosion resistance. They are used in jet engines, avionics, and missile components where heat is extreme . . . SmCo magnets remain stable at temperatures that would demagnetize other types, which is crucial for next-generation aircraft and weapons . . . If a system involves electric motion, sensing or high-powered electromagnetic emission, rare earth magnets are likely at its core." (n43) The Department of Defense has recently issued specific regulations (DFARS 225.7018) placing some restrictions on the procurement of certain rare earth magnets and related metals which will take effect over the next couple of years. As stated above, MP Materials does have plans for a magnet production facility, and the video below explains a bit more about that facility and the production of rare earth magnets. Rare Earths: A Challenge of Sustainability? REE-inclusive technologies, especially rare earth magnets, have become not only important defense industry components but also important components for green technologies such as wind turbines and electric vehicles. However, in the first video above, Amanda Lacaze, CEO and Managing Director of Australia's Lynas Corporation, a producer of rare earths, says "The whole ecosystem in which we are involved is ending up with product which is sold on the basis that they are good for the environment. Well, that is absolutely no good if we trash the environment along the way." In the MP Materials information presented, environmental stewardship and sustainability have been stressed as significant considerations in the company's mining and concentration operations to date. What remains to be seen in the future is whether or not there can be sufficient innovation and technological progress to be able to conduct rare earth separation and processing functions by current and future companies within the U.S. in ways which can be compatible with environmental regulations and concern for the areas in which they operate. FOOTNOTES - The following are the footnotes indicated in the text in parentheses with the letter "n" and a number. If you click the asterisk at the end of the footnote, it will take you back to the paragraph where you left off. n1 - The White House, Presidential Actions, Establishing the National Energy Dominance Council, Executive Orders, February 14, 2025, viewed September 2025 at www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/establishing-the-national-energy-dominance-council. (*) n2 - The White House, Fact Sheets, Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Takes Immediate Action to Increase American Mineral Production, The White House, March 20, 2025, viewed September 2025 at www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/03/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-takes-immediate-action-to-increase-american-mineral-production. (*) n6 - Reuters, "China Hits Back at US Tariffs with Export Controls on Key Rare Earth," as appeared in Yahoo Finance, April 4, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://finance.yahoo.com/news/china-hits-back-us-tariffs-115321661.html. (*) n7 - "China Tightens Rare Earth Grip in Retaliation to US Tariffs, Targeting Defense-Critical Elements," May 19, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://rareearthexchanges.com/news/china-tightens-rare-earth-grip-in-retaliation-to-u-s-tariffs-targeting-defense-critical-elements. (*) n8 - Kyiv Independent News Desk, "The Full Text of the US Ukraine Minerals Agreement," Kyiv Independent, May 1, 2025, viewed online September 2025 at https://kyivindependent.com/the-full-text-of-the-us-ukraine-minerals-agreement. (*) n9 - Hannah Northey, "Trump's Mineral Megadeal is Bypassing US Laws," E&E News by Politico, viewed September 2025 at www.eenews.net/articles/trumps-mineral-megadeal-is-bypassing-us-laws. (*) n10 - MP Materials, 8-K form filing with the Securities Exchange Commission, July 9, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001801368/6191cf7a-1cb7-4c45-a50a-72c98a0fbe86.pdf. (*) n11 - Northey, "Trump's Megadeal is Bypassing US Laws." (*) n13 - Gordon B. Haxel, James B. Hedrick and Greta J. Orris, "Rare Earth Elements - Critical Resources for High Technology," U.S. Department of the Interior/U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), USGS Fact Sheet 087-02, 2002, p. 2. (*) n15 - Bicker, Laura, "Poisoned Water and Scarred Hills: The Price of the Rare Earth Metals the World Buys from China," BBC News, China Rare Earths: The BBC Visits the World's Mining Capital for the Metals, updated 8/7/25, viewed September 2025 at bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-66cdf862-5e96-4e6e-90b8-a407b597c8d9. (*) n16 - Ernest Scheyder, The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives, New York: One Signal Publishers, 2024, p. 104. (*) n17 - Wikipedia, Rare-Earth Element Wiki, viewed online September 2025 at https://en.wikipedia.or/wiki/Rare-earth_element. (*) n18 - Carolyn Gramling, "Rare Earth Mining May Be the Key to Our Renewable Future. But at What Cost?" Science News online, January 11, 2023, viewed September 2025 at www.sciencenews.org/article/rare-earth-mining-renewable-energy-future. (*) n19 - Scheyder, The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives,, p. 105. (*) n20 - Heidi Crebo-Rediker, "America's Most Dangerous Dependence," Foreign Affairs, May 7, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/americas-most-dangerous-dependence. (*) n21 - Scheyder, The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives,, p. 107 - 108. (*) n22 - Rare Earth Exchanges, "Bayan Obo Mine: The Unseen Power Behind Global Technology- and Its Heavy Cost," April 27, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://rareearthexchanges.com/news/bayan-obo-mine-the-unseen-power-behind-global-technology-and-its-heavy-cost. (*) n23 - Tse, Pui-Kwan, China's Rare-Earth Industry, U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 2011-1042, Reston, Virginia: 2011, p. 1. (*) n26 - Mining Visuals, "Global Rare Earth Metals Production 2023," viewed September 2025 at https://www.miningvisuals.com/post/chinas-dominance-in-rare-earth-production. (*) n27 - Carolyn Gramling, "Rare Earth Mining May Be Key to Our Renewable Future. But at What Cost?" Science News online, January 11, 2023, viewed October 2025 at https://www.sciencenews.org/article/rare-earth-mining-renewable-energy-future. (*) n28 - Feng, Emily, "How China Came to Rule the World of Rare Earth Elements," NPR, July 23, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://www.npr.org/2025/07/23/nx-s1-5475137/china-rare-earth-elements (*) n30 - Scheyder, The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives,, p. 113-114. (*) n31 - Heidi Crebo-Rediker, "America's Most Dangerous Dependence," Foreign Affairs, May 7, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/americas-most-dangerous-dependence. (*) n32 - U.S. Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025, Ver 1.2, Reston, VA: March 2025, pp. 144 - 145. (*) n33 - Scheyder, The War Below: Lithium, Copper and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives,, p. 121-122. (*) n34 - Melissa D. Firestone and Jada Garofalo, Esq., An Analysis of the Current Global Market for Rare Earth Elements," Wyoming: University of Wyoming School of Energy Resources Center for Energy Regulation and Policy Analysis (CERPA), January 2022, pp. 11 - 12. Document available at http://www.uwyo.edu/cerpa. (*) n35 - U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Renewable Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Critical Materials Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper, DOE/EE-2056, April 2020. Available at https://www.energy.gov/eere/amo/articles/critical-materials-supply-chain-white-paper-april-2020, p. 7. (*) n37 - U.S. Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025, p. 145. (*) n38 - Innovation News Network, "Phoenix Tailings Begin Production at US' First Rare Earth Refinery," March 31, 2023, viewed September 2025 at https://www.innovationnetwork.com/phoenix-tailings-begin-production-at-us-first-rare-earth-refinery/31383. (*) n39 - Gordon B. Haxel, James B. Hedrick and Greta J. Orris, "Rare Earth Elements - Critical Resources for High Technology," p. 1. (*) n40 - U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), "Critical Materials: Action Needed to Implement Requirements That Reduce Supply Chaine Risks," GAO-24-107176, Q&A Report to Congressional Committees, September 10, 2024, p. 1. (*) n41 - Natural Resources Canada, "Rare Earth Elements Fact," updated 9/19/2025, viewed September 2025 at https://natural-resources-canada.ca/minerals-mining/mining-data-statistics-analysis/minerals-metals-facts/rare-earth-elements-facts. (*) n42 - Nikk Ogasa, "How Rare Earth Elements' Hidden Properties Make Modern Technology Possible," Science News online, January 16, 2023. Viewed September 2025 at https://www.sciencenews.org/article/rare-earth-elements-properties-technology. (*) n43 - Rare Earth Exchanges, "6 Military Uses of Rare Earth Elements in Defense Technology," October 4, 2025, viewed October 2025 at https://rareearthexchanges.com/rare-earth-elements-in-defense-technology. (*) LINKS INCLUDED IN ESSAY - The following are links included in the essay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY - The following is the Bibliography for the September 2025 essay. Asian Metal, Metalpedia, Rare Earths, Uses, viewed online September 2025 at http://metalpedia.asianmetal.com/metal/rare_earth/application.shtml Beiser, Vince, Power Metal: The Race for the Resources That Will Shape the Future, New York: Riverhead Books, 2024. Borowsky,Larry, "Sourcing Rare Earths and Critical Materials," Mines Magazine, date unspecified, viewed online September 2025 at https://minesmagazine.com/1737 Bicker, Laura, "Poisoned Water and Scarred Hills: The Price of the Rare Earth Metals the World Buys from China," BBC News, China Rare Earths: The BBC Visits the World's Mining Capital for the Metals, updated 8/7/25, viewed September 2025 at bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-66cdf862-5e96-4e6e-90b8-a407b597c8d9 Crebo-Rediker, Heidi, "America's Most Dangerous Dependence," Foreign Affairs, May 7, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/americas-most-dangerous-dependence Feng, Emily, "How China Came to Rule the World of Rare Earth Elements," NPR, July 23, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://www.npr.org/2025/07/23/nx-s1-5475137/china-rare-earth-elements Firestone, Melissa D. and Garofalo, Jada, Esq., An Analysis of the Current Global Market for Rare Earth Elements," Wyoming: University of Wyoming School of Energy Resources Center for Energy Regulation and Policy Analysis (CERPA), January 2022. Document available at http://www.uwyo.edu/cerpa Gramling, Carolyn, "Rare Earth Mining May Be the Key to Our Renewable Future. But at What Cost?" Science News online, January 11, 2023, viewed September 2025 at www.sciencenews.org/article/rare-earth-mining-renewable-energy-future Haxel, Gordon B., Hedrick, James B. and Orris Greta J., "Rare Earth Elements - Critical Resources for High Technology," U.S. Department of the Interior/U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), USGS Fact Sheet 087-02, 2002 Innovation News Network, "Phoenix Tailings Begin Production at US' First Rare Earth Refinery," March 31, 2023, viewed September 2025 at https://www.innovationnetwork.com/phoenix-tailings-begin-production-at-us-first-rare-earth-refinery/31383 Kyiv Independent News Desk, "The Full Text of the US Ukraine Minerals Agreement," Kyiv Independent, May 1, 2025, viewed online September 2025 at https://kyivindependent.com/the-full-text-of-the-us-ukraine-minerals-agreement Mining Visuals, "Global Rare Earth Metals Production 2023," viewed September 2025 at https://www.miningvisuals.com/post/chinas-dominance-in-rare-earth-production Natural Resources Canada, "Rare Earth Elements Fact," updated 9/19/2025, viewed September 2025 at https://natural-resources-canada.ca/minerals-mining/mining-data-statistics-analysis/minerals-metals-facts/rare-earth-elements-facts Northey, Hannah, "Trump's Mineral Megadeal is Bypassing US Laws," E&E News by Politico, viewed September 2025 at www.eenews.net/articles/trumps-mineral-megadeal-is-bypassing-us-laws Ogasa, Nikk "How Rare Earth Elements' Hidden Properties Make Modern Technology Possible," Science News online, January 16, 2023. Viewed September 2025 at https://www.sciencenews.org/article/rare-earth-elements-properties-technology Pitron, Guillaume, The Rare Metals War, (translation by Bianca Jacobson), London: Scribe Publications, 2020. Rare Earth Exchanges, "6 Military Uses of Rare Earth Elements in Defense Technology," October 4, 2025, viewed October 2025 at https://rareearthexchanges.com/rare-earth-elements-in-defense-technology Rare Earth Exchages, "Bayan Obo Mine: The Unseen Power Behind Global Technology- and Its Heavy Cost," April 27, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://rareearthexchanges.com/news/bayan-obo-mine-the-unseen-power-behind-global-technology-and-its-heavy-cost Rare Earth Exchages,"China Tightens Rare Earth Grip in Retaliation to US Tariffs, Targeting Defense-Critical Elements," May 19, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://rareearthexchanges.com/news/china-tightens-rare-earth-grip-in-retaliation-to-u-s-tariffs-targeting-defense-critical-elements Reuters, "China Hits Back at US Tariffs with Export Controls on Key Rare Earth," as appeared in Yahoo Finance, April 4, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://finance.yahoo.com/news/china-hits-back-us-tariffs-115321661.html Scheyder, Ernest, The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives, New York: One Signal Publishers, 2024. Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), MP Materials, 8-K form filing with the Securities Exchange Commission, July 9, 2025, viewed September 2025 at https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001801368/6191cf7a-1cb7-4c45-a50a-72c98a0fbe86.pdf Tse, Pui-Kwan, China's Rare-Earth Industry, U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Report 2011-1042, Reston, Virginia: 2011 U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Renewable Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Critical Materials Rare Earths Supply Chain: A Situational White Paper, DOE/EE-2056, April 2020. Available at https://www.energy.gov/eere/amo/articles/critical-materials-supply-chain-white-paper-april-2020 U.S. Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey/Daniel J. Cordier, 2020 Minerals Yearbook: Rare Earths [Advance Release], Reston, VA: June 2025 U.S. Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2025, Ver 1.2, Reston, VA: March 2025 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), "Critical Materials: Action Needed to Implement Requirements That Reduce Supply Chaine Risks," GAO-24-107176, Q&A Report to Congressional Committees, September 10, 2024 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, Changing Battery Chemistries and Implications for Critical Minerals Supplu Chains, UNCTAD/DITC/COM/2025/1, New York: United Nations, 2025 Wayman, Erin, "Recycling Rare Earth Elements is Hard. Science is Trying to Make It Easier," Science News [Online], January 20, 2023, viewed online September 2025 at www.sciencenews.org/article/recycling-rare-earth-elements-hard-new-methods The White House, Fact Sheets, Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Takes Immediate Action to Increase American Mineral Production, The White House, March 20, 2025, viewed September 2025 at www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/03/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-takes-immediate-action-to-increase-american-mineral-production The White House, Presidential Actions, Establishing the National Energy Dominance Council, Executive Orders, February 14, 2025, viewed September 2025 at www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/establishing-the-national-energy-dominance-council Wikipedia, Rare-Earth Element Wiki, viewed online September 2025 at https://en.wikipedia.or/wiki/Rare-earth_element

"Like" www.dorothyswebsite.org on FACEBOOK! Home | Essays | Poetry | Free Concerts | Website Book Page | Arts/Events | About the Site | News |

|||

| ||||

|

www.dorothyswebsite.org © 2003 - 2026 by Dorothy A. Birsic. All rights reserved. Comments? Questions? Send an e-mail to: information@dorothyswebsite.org | ||||